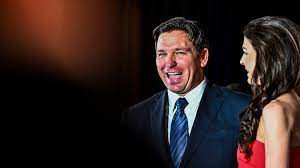

Ron DeSantis is set to join the 2024 campaign amid high Republican hopes that he’s precisely the kind of conservative who can knock off President Joe Biden. But the odds are stacked against him.

The problem isn’t really Biden, or even former President Donald Trump, who leads the Florida governor in early GOP polls. It’s his state and the weight of history.

No Florida politician has ever been elected president. A half-dozen have run in the last 50 years — essentially the period in which the state evolved from political backwater to electoral powerhouse — but all have ended up in the same place, dead in the water long before the nominating convention. Most never even made it past New Hampshire’s first-in-the-nation primary.

The curse of Florida Man — and to date, every Florida presidential candidate has been male — lingers despite the fact that the state is an ideal proving ground for a White House bid. Winning statewide office requires campaigning in two time zones, 10 TV markets, and across 66,000 square miles. It is home to more than 22 million people — many of them arrivals from other states, which gives Florida politicians exposure to a wide range of political customs and styles.

It’s a curious predicament for the nation’s third-largest state. Florida does have some White House connections, of course. Presidents have retired there. They’ve owned vacation homes there. Trump himself moved there midway through his first term as president, changing his official residence from Manhattan to Palm Beach.

But in the nearly 180 years since Florida was admitted to the Union, it has neither produced a president nor had one born within its borders. (No, Andrew Jackson’s pre-statehood stint doesn’t count.) It is the lone state among the nation’s 10 most populous that has never sent anyone to the White House.

Texas, which became a state nine months after Florida, can point to three presidents — four, if you count Dwight Eisenhower, who was born in Denison. California, which achieved statehood five years after Florida, has produced two. Even Hawaii, the last state to be admitted to the Union in 1959, can boast a presidential pedigree, with the birthplace of Barack Obama.

The absence of Florida’s presidential bragging rights shouldn’t be a complete surprise. It stems, at least in part, from the low esteem in which Florida — and its politicians — were held for the first century of its existence and perhaps beyond.

When the writer John Gunther took stock of the nation and its politics in the 1940s for his panoramic book, Inside U.S.A ., he noted that Florida’s “freakishness in everything from architecture to social behavior [is] unmatched in any American state.”

“Sometimes people compare California to Florida,” Gunther wrote of the nation’s sun-drenched states, “but from an intellectual point of view, there is no comparison.”

At mid-century, V.O. Key, Jr., in his political science classic, Southern Politics , observed that Florida was a politically atomized and unorganized state, “an incredibly complex mélange of amorphous factions,” with few politicians who could exert influence beyond their own county.

Florida, he wrote, “is not only unbossed, it is also unled.”

By the 1970s, though, that began to change. Decade after decade of runaway population growth had swelled the state’s population ; in the 1950s alone, Florida’s population nearly doubled in size. State constitutional revisions in 1968 finally enabled governors to serve more than one term. Not long after, the state started producing top homegrown talent, from both parties, and sending them to the national dance.